Early Efforts to Set aside Parkland and Late Investments Made Como Park What It Is Today.

How Was Como Park Established?

In the 1870s, the well-respected landscape architect Horace W. S. Cleveland urged growing cities to set aside land for public parks before land prices skyrocketed. Large parks were considered desirable assets for the health and enjoyment of urban dwellers. At the City of Saint Paul’s request, Cleveland identified many natural features in Saint Paul worthy of preservation as parkland, including the land around Como Lake.

An 1872 bond issue of $100,000 allowed Saint Paul to purchase nearly 260 acres of land near Como Lake for a major public park. The City bought 40 acres of land from Frank E. Clark, 193.55 acres from William R. Marshall, and 26.4 acres from William B. Aldrich (who owned a hotel at the lake).

After its purchase, an economic downturn caused the park to lay dormant for 14 years. Some called for its sale, but the City held onto the parcel. By 1887, funds were finally available. A park board was created, and Cleveland was hired to design Saint Paul’s parks and parkways. Cleveland envisioned a landscape park that brought out the “innate grandeur and beauty” of the natural features within it. He designed curving roads to bring carriages past points of beauty. Over the next few years, implementation of his grand plans began.

The bulk of construction and layout of the park was completed during Frederick Nussbaumer’s 30-year superintendency (1891–1922). Nussbaumer embraced the popular idea that parks should offer playgrounds for organized, active recreation as well as natural beauty. In addition to many ornamental features, such as floral display gardens, lily and lotus ponds, a Japanese garden, and a spectacular glass-domed conservatory, ball fields and tennis courts were added.

Hard Times for Como Park

W. LaMont Kaufman served as park superintendent for 33 years (1932– 1965). He held the park together through the Great Depression and World War II, and the periods of insufficient budgets afterwards. He used makeshift methods to keep the conservatory from falling into total disrepair, opposing those who deemed it an unnecessary “luxury.” During the war, he and the zookeeper would take their own cars to collect food from stores and hotels for the zoo animals.

City officials recommended closing the zoo in 1955, but a citizen’s volunteer committee fought to keep it open.

As the park system and demand for services grew, funds often did not keep pace. World events and economic downturns limited further development and high-maintenance features were removed or faded away. Vandalism became a problem. The long period of stagnation and decline began to slowly and steadily improve after the completion of a master plan for the zoo in the mid–1970s and a Como Park Master Plan in 1981.

Como Park Today

The period following the creation of the master plans has been one of improvement and renewal. Many roads have been removed to reduce traffic congestion and add green space. With more funds available through private donations, federal sources, and two state constitutional amendments, many of the neglected ornamental features have been restored or rebuilt. Considerable improvements have been made throughout the park, including shoreline restoration, major upgrades to zoo and conservatory exhibits, and significant new building projects.

Photos

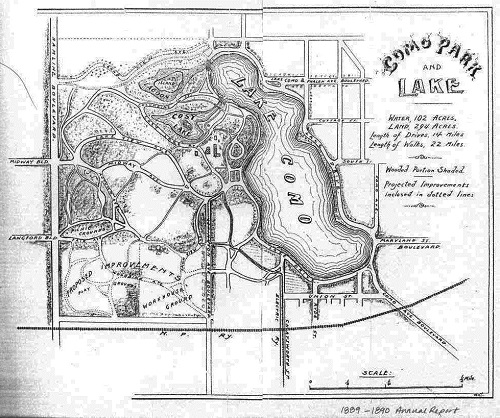

- Como Park and Lake Plan from 1889-1890. Photo: City of St. Paul

- Como Lakeside Pavilion. Photo: Steve Sundberg / CC BY-NC-ND

- Path along Como Lake. Photo: Sharyn Morrow / CC BY-NC-ND